Climate, housing, racial justice, energy, and a wide array of other social and environmental issues are topics driving the 2022 WA Legislative Session; topics that have historically fallen outside of the conservation movement’s scope, where conservation focused primarily on the preservation of land and natural resources. The challenges facing current and future generations – growing wealth inequality, continued environmental degradation, and climate change – demand more from all sectors: less siloing, more integrated planning, and systems-level thinking.

The conservation sector is poised to assume leadership in creating a more expansive and inclusive approach; embracing and acting upon these important intersections, which will grow the field’s sphere of influence and impact so that it meets the needs of modern times. Recently, members of the EA team participated in a national discussion about “The Future of Conservation,” which endeavors to create a new National Conservation Framework by integrating topics such as: Traditional Ecological Knowledge/Indigenous Knowledge, Collaboration, Private Lands (including working lands), Biodiversity, Climate Change, Urbanscape, and Government. It’s a compelling effort for those working in support of a new vision and framework for conservation.

This more expansive framework for conservation intersects with housing sustainability and justice; policy topics central to creating healthy, livable and sustainable communities. This blog introduces essential links between conservation and housing; recognizing both the impact that current housing systems and policies have on conservation efforts, and the role the conservation sector can play in promoting progressive land use policies that benefit people and the environment.

Housing History & Affordability:

The Puget Sound region, like many US metropolitan regions, was built according to the ideal of the American Dream, defined by the suburban single family home, yard, and garage. As a relatively new city on the west coast, Seattle grew when automobiles had already taken off and planners designed the city around the dominant use of cars and single family homes.

This car-centric, single family-oriented housing system has been increasingly under scrutiny for a host of negative impacts to both people and the environment: the declining health of Puget Sound (via stormwater runoff and loss of habitat), vanishing farms and forests (via urban sprawl), congested roadways, a lack of sustainable public transit systems, and a profound shortage of affordable housing. This approach to growth management and development has left our ever-growing region with decreased livability and accessibility, increased rental housing costs, and out of reach homeownership for the majority of workers. As of 2020, over 40% of renters in Washington are housing cost burdened, meaning that they spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Homeownership is increasingly inaccessible, which prevents intergenerational wealth accumulation and perpetuates inequity (for anyone especially interested in this topic, see the documentary “Owned: A Tale of Two Americas” and this free video game that communicates the illusion of choice and opportunity in the housing system).

At the same time, redlining in Seattle further exacerbated economic and environmental impacts on black and brown communities. Until HB 323 passed in 1977, banks could refuse to provide loans for properties in certain neighborhoods based on race. This promoted housing segregation and forced black and brown residents into underfunded, often industrial neighborhoods with more hardscape, less open space, less tree canopy, and more exposure to pollution. Redlining is a story of economic, racial, and environmental injustice that still impacts these communities today – gentrification displaces long-time residents by capitalizing on the neighborhoods’ affordability. And this exclusionary zoning is still directly tied to lack of natural resource investments – where there are lower income neighborhoods, there tends to be a lack of open space (see this 2016 tree canopy assessment for example).

Density & Growth Management:

Growing cities with dominantly single family, low-density zoned areas, Seattle included, struggle with housing affordability. The Puget Sound region’s challenges are heightened because of the relatively constrained geography presented by water, steep slopes, and the bounty of significant acres preserved in national parks, national forests, and state conservation lands. In conjunction with rapid population growth and exclusionary zoning that prioritizes single family zoning, this region’s livability and affordability are threatened.

Conservation efforts thrive when urban, suburban, and rural growth is managed in a way that promotes density and reduces sprawl. How we “do density” seems to be the crux of the challenge. How do we achieve a balance of housing options within designated growth areas (areas specifically designated to contain sprawl)? How do we build according to design standards that maximize the health of people, nature and community? And where can land conservation meaningfully interface in support of the needed reforms to existing zoning and development paradigms?

Solutions – Integrating Conservation & Housing:

First, let’s look at community land trusts as models for addressing land and homeownership affordability. Community land trusts like Homestead, Africatown, Lopez, and Community Land Conservancy provide desperately needed, permanently affordable homeownership opportunities. Community land trusts create new models of both land and home ownership that address the inequities in the current system while advancing both affordability and conservation priorities. How can traditional land trusts support the work of their counterparts in community land conservation?

Second, let’s talk about progressive land use policies. Faced with continued population growth over the next 30 years, the Puget Sound region must grapple with the fact that low density, single family housing is not sustainable from an environmental, economic, and human health standpoint. Embracing a more expansive view for achieving conservation objectives – where environmental justice, livability, and sustainability are inextricably linked to land use policies – simultaneously advances land conservation goals and the overall sustainability of our communities and landscapes.

These issues and policies are just a selection of some of the most current and relevant land use issues that intersect with the environment. Our housing development and land use system is deeply complex, and there are many more solutions beyond what’s acknowledged here. The Emerald Alliance for People, Nature and Community is emblematic of a more equitable, people-centered view of conservation. If we move forward with this mindset, we naturally shift our focus toward the many intersections between the health of natural systems and where we live, how we live, and how our societal systems are structured and overlapping. There is a lot of activism and policy momentum around land use, housing, and growth management (evidenced by the docket of legislative bills winding through the 2022 WA Legislative Session). The conservation sector is finding ways to lean into these intersections and learn where and how to support ever-growing win-win policy solutions.

Below are resources that highlight some of the more important and contentious topics in land use policy, many of which have bills that are currently being considered in the 2022 WA Legislative Session. We hope you find some inspiring nuggets that spur greater curiosity and engagement with these issues:

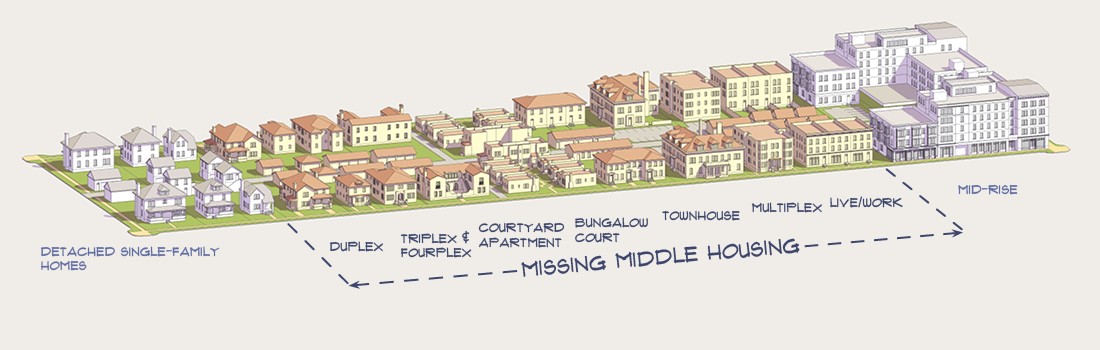

- Loosening restrictions on “missing middle” housing – small multifamily developments like duplexes, townhomes, rowhouses, and backyard cottages add housing and create density while maintaining neighborhood character. Seattle has relatively progressive policies already in place, but HB 1782 would establish statewide regulations that legalize and increase production of missing middle housing across the state.

- Updating the Growth Management Act – the GMA requires cities and counties to regulate housing affordability and urban sprawl, but three important bills have been introduced in the current legislative session that would incorporate climate emissions requirements, equity and racial sensitivity, and remove a vital loophole in the Act. This legislation and more is needed to ensure that the GMA evolves to meet the region’s needs.

- Promoting transit-oriented development – housing activists understand that we can’t replace entire cities with apartment buildings, but we must add density where there is better access to public transit. This positively impacts housing affordability, livability, and the environment (via less reliance on cars).

- Creating publicly owned affordable housing via Housing Benefit Districts – a currently introduced bill, HB 1880, would expand on existing Transportation Benefit Districts to provide funding for cities and counties to develop four pilot Housing Benefit Districts in Everett, Shoreline, Renton and Tacoma. Activists expect statewide authorization of Housing Benefit Districts will be introduced in 2023.

- Lowering parking ratios to reduce urban heat islands – extreme weather events are going to become the new norm, and this will impact people (particularly houseless people and disadvantaged communities) and the environment (for example, the heat wave’s impact on Oregon’s forests). Land use policies can help mitigate urban heat islands to provide a barrier against these impacts.

Recent Comments